Up on the upper deck of a navy ship in the late 1950s, back to the blast, listening to the countdown to detonation.

First was the flash, then a rolling thunderclap swept across the ocean a minute or so later.

When the flash came and their backs were to the blast, they were able to see an x-ray vision of their bones.

This is what many New Zealand Navy sailors experienced between May 1957 and September 1958.

British Nuclear testing, “Operation Grapple” involved nine tests near Christmas Island.

Recently, two Navy veterans received medals from the British Government who finally recognised their efforts in Operation Grapple between May 1957 and September 1958.

Naval officer commander Keith Wisneskey presents the medal to Ronald Arther Francis Owen. Photo: Ayla Yeoman.

Naval officer commander Keith Wisneskey presents the medal to Ronald Arther Francis Owen. Photo: Ayla Yeoman.

Ronald Arther Francis Owen – also known as Raf, official number Q13952 – joined the Navy in September 1951 as a Boy 2nd Class.

In 1957 he was on board the HMNZS Pukaki where he witnessed two nuclear detonations – Grapple X and Y.

Gordan Lindsay Roberts – official number M16180 – joined the Navy in May 1957 as an ordinary seaman.

Lindsay’s first post was on the HMNZS Pukaki where the ship spent three months at Christmas Island for Operation Grapple, witnessing four nuclear detonations – Grapple Z.

“We were guinea pigs because they wanted to know how close you can put a ship to a nuclear detonation and still operate,” says Lindsay.

Keith Wisneskey presenting medal to Gordan Lindsay Roberts. Photo Ayla Yeoman.

Keith Wisneskey presenting medal to Gordan Lindsay Roberts. Photo Ayla Yeoman.

“You only saw the little ones!” joked New Zealand Nuclear Testing Veterans Association vice president Brian Harnor.

The biggest one was Grapple Y, which was the equivalent of three million tons of TNT which is 200 times bigger than Hiroshima, “and we were 80 miles away, but as per normal we were all on the upper deck and back to the blast”.

“We could hear the countdown to detonation.

“It was awe-inspiring,” says Brian.

“It is something you would never forget,” says Ronald.

“We had x-ray vision of our bones in our hands,” says Brian.

“You couldn’t believe it, can this be happening?

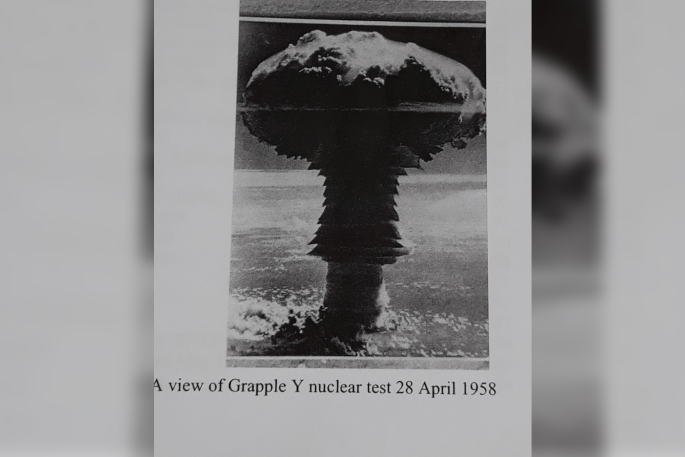

“Then, a couple of minutes later we were told we could turn around and then you saw this developing H-bomb well up in the sky and this big orange-coloured ball growing larger and larger. It was an amazing sight.

“You could see the sea being sucked up, we got this mushroom effect and it kept growing bigger and bigger at the top.

A view of Grapple Y nuclear test April 28, 1958. Photo supplied.

A view of Grapple Y nuclear test April 28, 1958. Photo supplied.

“It was just fantastic, I mean it’s just like a movie.

“The thought of damage or nuclear fallout or the future never entered our heads.

“We were there as weather ships to make sure that if there was any dirty fallout it would be blown away from any land mass,” says Brian.

Their task as sailors on the weather ships was to let off hydrogen balloons to monitor the weather and make sure it was safe to drop the bomb.

“They wouldn’t drop the bomb until it was safe.

“They said it was clean, but they weren’t sure, this was all an experiment.”

This medal ceremony was hugely significant to the veterans as they represented a recognition of their efforts from the British Government in British Nuclear Testing.

Any exposure to the use or testing of nuclear weapons exposes you to radiation.

The exposure that these veterans have been exposed to is incredibly dangerous causing cancers and many other health implications for those exposed and the generations after them.

“In 1945 they had Hiroshima, Nagasaki, they knew the effect of those detonations,” says Lindsay.

“They were testing a new generation of bombs that they hoped were safe, but they had to test them to find out,” says Brian.

“We were totally uninformed about the possible health hazards,” says Brian.

“We were there doing a job to which they said there was no danger, says Lindsay.

“The scientists knew there was danger.

“They were aware there was radiation danger.

“We were just the minions, the guinea pigs.”

Medal presentation ceremony attendees. Photo Ayla Yeoman.

Medal presentation ceremony attendees. Photo Ayla Yeoman.

Due to the harm that these veterans were exposed to, Britain, the Royal Navy, the Air Force and the government have played hardball and denied all claims of harm caused by the exposure of their nuclear testing.

“They’ve always hid the facts and denied them,” says Brian.

Brian says around three years ago Boris Johnson sat down with the British veterans and finally looked them in the eye.

Finally, he understood the pain and realised what these guys had gone through, says Brian.

“Out of that meeting, this medal was created."

Hence why the design of the medal has an atom surrounded by olive branches, explains Keith.

Brian did not receive a medal on Thursday, February 22, as he will be presented with his Tuesday, February 27 by the British High Commissioner.

“Next Tuesday at the Navy Museum in Auckland, the British High Commissioner is honouring us by coming to that function, and she will honour us by presenting it to us on behalf of the British government.

“That makes me very proud that they’ve recognised the service, it’s been a long, long time coming,” says Brian.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.