Lions stuck in “filthy” cages on canned hunting farms, bred to be bought and shot by foreign trophy hunters. A black market of lion bones.

Farmers overbreeding lionesses, which produce deformed, paralysed cubs. These are some of the heartbreaking tales a New Zealand ranger has from doing conservation work in South Africa, where there are about 8000 to 12,000 lions farmed in commercial facilities, compared with an estimated 3000 in the wild, according to World Animal Protection.

Being stalked by lion breeders has not dampened a Kiwi’s enthusiasm to save wildlife in South Africa.

Instead, Tauranga’s James Dorrington says he's itching to get back to continue trying to save the lives of vulnerable animal species including lions, elephants and rhinos.

The 28-year-old says he's part of a team of New Zealanders that saved two lions being kept in small, “filthy” cages with old food carcasses and piles of faeces on a canned hunting farm, breeding lions for trophy hunting.

The group relocated the lions to a sanctuary in Zimbabwe.

But the previous rescue mission did not have such a happy ending, with James left afraid to return to the country after his social media was tracked down and people he believed had links to lion farming pressed his friends for information.

He says a peaceful negotiation between his team and farmers to release captive lions went downhill after information identifying the farmers was made public.

“These deals are made based on the breeders staying anonymous so when the public found out and started protesting against them, the deal was off,” says James.

When he returned home to New Zealand, his friends started receiving strange messages.

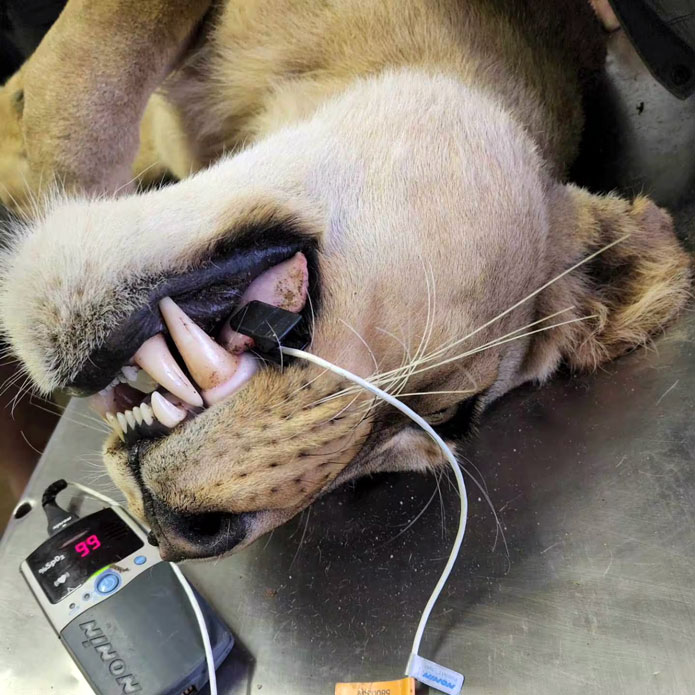

James Dorrington rescued and relocated two lionesses.

James Dorrington rescued and relocated two lionesses.

He says he believes lion breeders are behind fake social media accounts posing as James’ relatives, asking his friends questions about when he's flying in and to which airport in South Africa.

The ranger describes them, in his view, as “scary” and “dangerous” people who are “very good at getting information”.

James says it blew over in about a month and when he's called to help with the second lion mission, he said yes.

“There was quite a bit of nerves around initially landing there by myself but I knew once I got on to the reserve and I got with my team, everything would be all right.”

He would not reveal further details about his team to protect their work.

James says at the trophy-hunting farm there are about 20 other lions they couldn't save due to not having enough resources. There are also spotted hyenas, a warthog, meerkat, monkey and baboon.

It's a “tense” and “unsettling” environment, and for many involved it was their first time seeing animals in those conditions.

“We didn’t know what we were going into but thankfully everything went smoothly.”

He says the hardest thing is knowing he couldn't help the other animals on the farm.

Zoologist Sinead Ellis is a volunteer involved in the mission and she says the lions seemed to know they were in a “good place” once they were in their new enclosure.

The conditions they found the lions in were “not as bad as she thought”.

The lions did not have any serious health problems despite having been kept in small cages.

The lions did not have any serious health problems despite having been kept in small cages.

But Sinead says they were not ideal with the two lions together in a small cage that was not regularly cleaned.

She says the lions didn't have any health problems and were bred to look “plump” and “healthy” for trophy hunters.

Sinead was shocked to see a cub in the same cage as a monkey and a meerkat.

Canned hunting farms

James says lion cubs were torn away from their mothers in captivity at a couple of weeks old to be used in tourist petting areas, with their owners unaware this got the animals used to human interaction and made them easier to hunt for trophies later.

The lionesses were forced to breed quicker than the norm of one cub every two years and would often have cubs with Down syndrome or paralysis.

James says trophy hunting is most popular with American visitors to South Africa, where people will pay between $80,000 and $100,000 depending on the animal’s size, to shoot and pose with their kill.

After a lion is hunted, farmers illegally smuggled and sold parts of the animal’s body on a black market in Asia, where some people believed their bones had healing qualities.

From the Navy to the Savannah

After James finished up in the Royal New Zealand Navy in 2021, he wanted to find purpose again in his life and decided to fly to South Africa, where heworked with orphaned elephants.

He says he “fell in love with the work” after seeing how the animals responded to his help.

“It’s really weird. You can recognise they’re thankful for you, know who you are, and see you’re working to help them,” says James.

He says he studied nature building at The Nature College for three months to become a qualified ranger.

He had to return home after his studies because his visa ran out. He was applying for a long-term working visa so he could stay in the country longer.

“It’s an issue that I see as much bigger than myself and it feels good doing something to help that.”

Back in New Zealand, Dorrington said he worked with Bay Conservation Alliance monitoring the native plant and bird species around the forests.

He says the work was “completely different” to South Africa and is “a lot more quiet and safe”.

James wants to get back to South Africa as soon as possible and had set up a Givealittle page for his future wildlife conservation work.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.