A five-year global research programme has reached the Hauraki Gulf with scientists aiming to determine the seabed’s ability to store carbon and support biodiversity.

University of Exeter scientists from the United Kingdom are on the water for a month taking samples at various points of the cable protection area.

Sediment samples are frozen and sent for analysis in an effort to establish differences in existing protection inside and outside the CPA where there is evidence of trawling activities.

Any signs of life are placed into ethanol and sent for analysis.

The research comes under the umbrella of the Convex Seascape Survey, being undertaken around the globe, with 100 experts involved in the project.

The programme is largely funded by insurance tycoon and philanthropist Stephen Catlin, chairman of Convex Insurance.

A team of three UK scientists are based at Leigh, north of Auckland, working with University of Auckland staff at the Leigh Marine Laboratory for UK-based ocean conservation charity the Blue Marine Foundation.

The Hauraki Gulf was identified as ideal for the study because it has protected soft-sediment habitats next to areas affected by trawling, less than 100m deep, and with muddy seabeds.

Dr Ben Harris, from left, with PhD students Tara Williams and Mara Fischer at work in the Leigh Marine Laboratory. Photo / Al Williams

Dr Ben Harris, from left, with PhD students Tara Williams and Mara Fischer at work in the Leigh Marine Laboratory. Photo / Al Williams

Led by Dr Ben Harris, and PhD students Mara Fischer and Tara Williams, the project is labour-intensive.

Harris is a marine ecologist and graduate from Victoria University in Wellington. He has expertise in the ecological functions of temperate benthic communities, small animals that live on or in the bottom of bodies of water.

His work as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Exeter investigates the impact of human disturbance on benthic communities and their ability to uptake and sequester carbon.

Harris says he is exploring questions that will help answer how human disturbance, such as trawling and dredging, influence the processes of blue carbon uptake, storage, and loss from ocean seascapes.

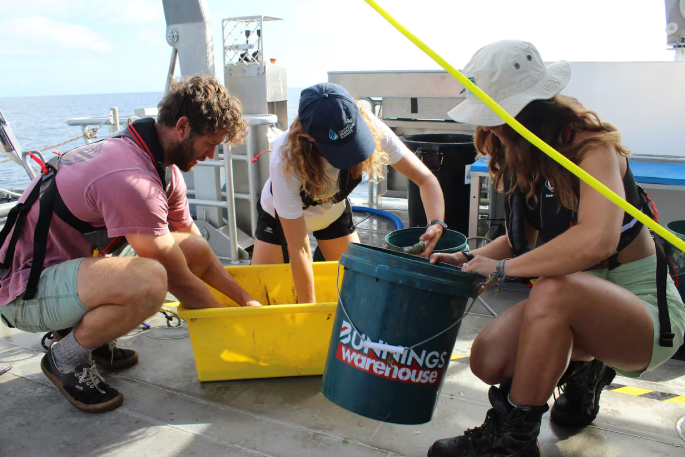

Tara Williams and Mara Fischer sift through the sediment looking for signs of life. Photo / Al Williams

Tara Williams and Mara Fischer sift through the sediment looking for signs of life. Photo / Al Williams

The research could influence debate over the expansion of and creation of marine protection zones, potentially driving economic growth.

The work employs a variety of techniques including remotely operated underwater video, baited remote underwater video, scuba, and groundbreaking vibro-corers which extract the sediment samples.

In the Hauraki Gulf, eight sites have been identified.

Harris says the paired sites will allow for a comparison of areas under protection and those subjected to high trawling activity.

The baited remote underwater videos capture footage of benthic fish and invertebrate communities, while grab sampling assesses infauna within the sediment.

Ben Harris controls a remotely operated vehicle, observing the ocean floor. Photo/Al Williams

Remotely operated video surveys are being used to study animals living on the seabed, while vibro-coring, which uses a vibrating core tube, will allow researchers to measure the amount of carbon stored in the seabed, up to 1m.

Harris says the research aligns with New Zealand’s conservation goals, particularly revitalising the Hauraki Gulf, aimed at reversing ecological degradation in the stretch of water. The study will contribute to the planned national marine sediment carbon inventory by the National Institute of Water and Atmosphere (Niwa).

Through collaboration with the Department of Conservation and other stakeholders, the survey would eventually provide data that is crucial for sustainable marine management and advancing blue carbon science, he says.

Harris says evidence in the Hauraki Gulf is overwhelming from what he has already seen. “I’m really shocked about how much stuff is inside the cable site.”

It’s a six-week window for the trio, working on board the University of Auckland research vessel Te Kaihōpara.

While grab sampling will be sent to Niwa for analysis, the frozen sediment samples will be sent to Exeter where the painstaking research will continue.

Much of it appears to be literally sifting through sediment with a fine-tooth comb.

Te Kaihōpara is skippered by Auckland University Faculty of Science senior technician Brady Doak. Photo / Al Williams

Harris says it’s “contentious” research and politics often stands in the way.

“You are setting out to measure it, Blue Marine Foundation have an agenda, it’s a good agenda.”

Te Kaihōpara is skippered by Auckland University Faculty of Science senior technician Brady Doak, with support from senior technician Paul Caiger.

The pair share decades of experience in the Hauraki Gulf.

Caiger is the Auckland University dive safety officer. He’s the author of Fishes of Aotearoa, an illustrated book with descriptions of fish life in New Zealand.

Auckland University Faculty of Science senior technician Paul Caiger shows Ben Harris a chart of the Hauraki Gulf. Photo / Al Williams

Auckland University Faculty of Science senior technician Paul Caiger shows Ben Harris a chart of the Hauraki Gulf. Photo / Al Williams

Meanwhile, Harris describes New Zealand as a shining example of “great marine protection areas”.

He has undertaken similar studies in the United Kingdom where he says such areas are almost non-existent.

Telecommunications giant Spark is also keeping an eye on things, he says, as it oversees the CPA.

“I message Spark each day and let them know where we are, it gives them an opportunity to monitor what we are doing.”

It’s another considerable responsibility given the potential consequence of disturbing the CPA, he says.

“Any anchoring in the cable zone has to be permitted.”

Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island pictured from the bridge of Te Kaihōpara. Photo / Al Williams

Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island pictured from the bridge of Te Kaihōpara. Photo / Al Williams

Today’s sailing is within the vicinity of Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island, with samples taken at a depth of about 50m.

While Harris describes human impact in the gulf as not as intense as elsewhere, he labels it “ecologically collapsed”.

“The lobster fishery is functionally extinct; the snapper fishery is way done, the scallop fishery is hammered.”

The researchers will spend 30 days on the vessel taking samples.

“You have to make sure it is consistent; it’s a flyover which captures everything.

“Looking at everything below and above the seabed, we are trying to get a holistic image, an overall picture.”

The samples are placed straight into ethanol and will be analysed. Photo / Al Williams

He says there have been surprises.

“Some patches of the seabed that are quite rich in life, a lot of stuff growing out of the seabed.”

Analysis of the vibro-coring, taken and analysed in “slices” will likely tell stories, thousands of years in the making, he says.

Harris helped design and build a frame to stabilise the vibro-corer on the open ocean.

“We built a modified frame to hold it in place, it worked pretty well, it’s going to be a game changer,” he says.

Ben Harris, Mara Fischer and Tara Williams will spend long hours sifting through sediment to find samples. Photo / Al Williams

Ben Harris, Mara Fischer and Tara Williams will spend long hours sifting through sediment to find samples. Photo / Al Williams

While Williams is focusing on invertebrate communities, Fischer is looking at fish communities.

“It’s a massive area of research, alongside it is the question if there is a link between the life that sits around the seabed and carbon in the seabed.

“This research is a way of ground truthing that trawling is at least impacting the seabed to hold carbon.

“We know that trawling, sweeping and dredging affects it, even though we know it, legislation has not been that good globally.

“We have the potential to expand marine protected areas; it’s a better selling point.

“If you have an organisation that has a massive carbon footprint, they could be more inclined to invest.

“It’s potentially creating an economy.”

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.