Posted: 10:30am Sun 21 Mar, 2021

Research finds microplastics in fish muscle tissue

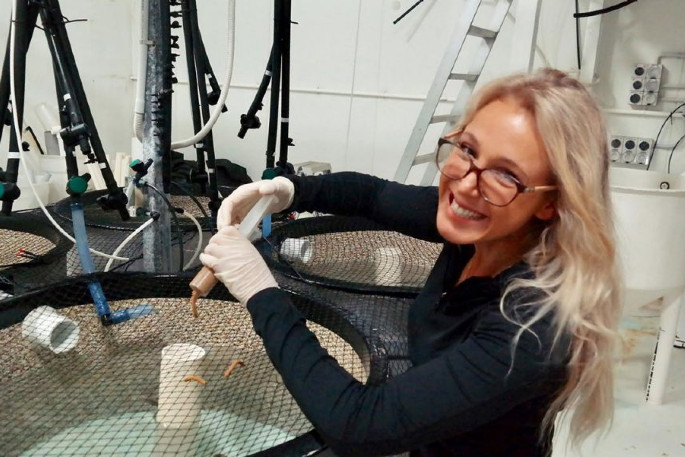

Veronica Rotman feeding fish in NIWA's Bream Bay laboratory as part of her work into whether fish are absorbing microplastcs. Photo: NIWA.

Some of the first research into how microplastics are affecting New Zealand fish species has revealed that microplastic fragments can find their way through the gut lining and into muscle tissue.

Experiments carried out by two masters students from the NIWA and University of Auckland Joint Graduate School of Coastal and Marine Science have shown that some fish species ingest more microplastics than others in the Hauraki Gulf, but that almost 25 per cent of all fish sampled had microplastics in their guts.

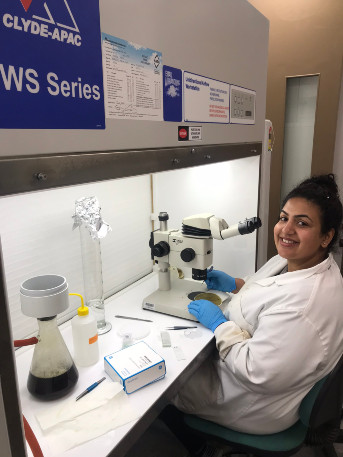

Microplastics are defined as pieces of plastic less than 5mm long and are either manufactured to be small or derived from larger plastics that have broken down into smaller pieces. Identifying them in

fish gut samples requires specialised laboratory equipment and protocols to ensure all potential

sources of contamination are eliminated.

Devina Shetty focused on six fish species commonly found within the Gulf: snapper, yellowbelly flounder, gurnard, jack mackerel, kahawai and pilchard. Microplastics were found in 70 of 305 fish specimens, which included more than half of the yellowbelly flounder sampled.

"This higher ingestion rate for flounder could be due to microplastics accumulating in marine

sediments which makes up more of their diet compared to other species, or it could be because the

flounder samples were all obtained from the Waitemata Harbour, which is closer to Auckland as a

potential microplastic source," says Devina.

Devina says she is surprised by the results.

"As an island nation in the South Pacific with relatively low population numbers you would expect to see lower ingestion rates so I was a bit surprised when half of the flounder species had ingested mostly microfibers. However, given that they were caught near Waitemata Harbour, which is closer to Auckland as a potential microplastic source and are a benthic species (70 per cent of plastics sink to the bottom of the seafloor) it makes sense."

Devina Shetty examing fish for microplastic injestion. Photo: NIWA.

Veronica Rotman focused on hoki from the West Coast of the South Island, Cook Strait and the

Chatham Rise. One or more microplastics were found in the stomachs of 95 per cent of the 60 fish

examined, with 90 per cent of the particles identified as fibres.

Veronica also completed a ten-week tank experiment at NIWA's Northland Marine Research

Centre in which snapper were fed a diet containing polystyrene microplastic feed at different

concentrations. She found that those fed a higher concentration were more likely to have

microplastic in their white muscle tissue.

"This suggests that ingested microplastics can translocate from the gut and into the muscular tissue

in small numbers (1-2 per fish) at tiny sizes, potentially making that plastic available to anything that eats that muscle tissue, whether it be larger fish or potentially humans."

Veronica also observed significant inflammatory, vascular and structural changes to the intestine

with only a low ‘environmentally relevant' microplastic treatment, suggesting that similar damage is

occurring in the wild. The damage to the intestine increased with microplastic concentration, with

60 per cent of high treatment fish displaying severe alterations.

While this gut damage didn't lead to any significant effects on growth or mortality in the ten week

experiment conducted, it demonstrates that microplastic has significant negative effects on the fish

that eat it.

"The intestine is fundamental for the absorption of nutrients and changes to the structure found in

this experiment would ultimately impair nutrient absorption and growth in the long term. Further

ingestion of microplastics may compromise the permeability, efficiency and immunological response

of the digestive tract affecting organ function, reproductive success, growth and ultimately,

survival".

NIWA fisheries scientist Dr Darren Parsons, who oversaw the projects, said there had only been one

previous study looking at the effects of microplastics on New Zealand fish species and these studies

provided some valuable insight into what has become an issue of huge concern.

"Microplastics are found throughout the world's oceans, even in Antarctica. They pose a unique

threat to marine life."

The next steps in this research would be to focus on the microfibres that are the most common type

of microplastic found in the ocean, and to conduct more comprehensive experiments to establish

the long-term effects of microfibres on fish.

0 comments

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to make a comment.